The Great Bear Constellation

The Great Bear Constellation is one of the first constellations children learn about as they gaze into the night skies. Ursa Major is relatively easy to spot because there are only two more prominent constellations. It is even easier when you look for another celestial favorite within the star group, the Big Dipper.

This asterism is the Northern Hemisphere’s most recognizable star group and part of the Great Bear. The Big Dipper makes up the Bear’s hindquarters and tail.

Great Bear tales weave through ancient stories across cultures. Greek mythology’s Callisto to Native American legends enrich our understanding of the night sky.

There are so many exciting stars and groupings in and near Ursa Major. So, let’s jump right in to learn more about this famous constellation.

But first, check out this 1690 illustration from Johannes Hevelius’ Uranographia.

Table of Contents

Ursa Major: A Celestial Overview

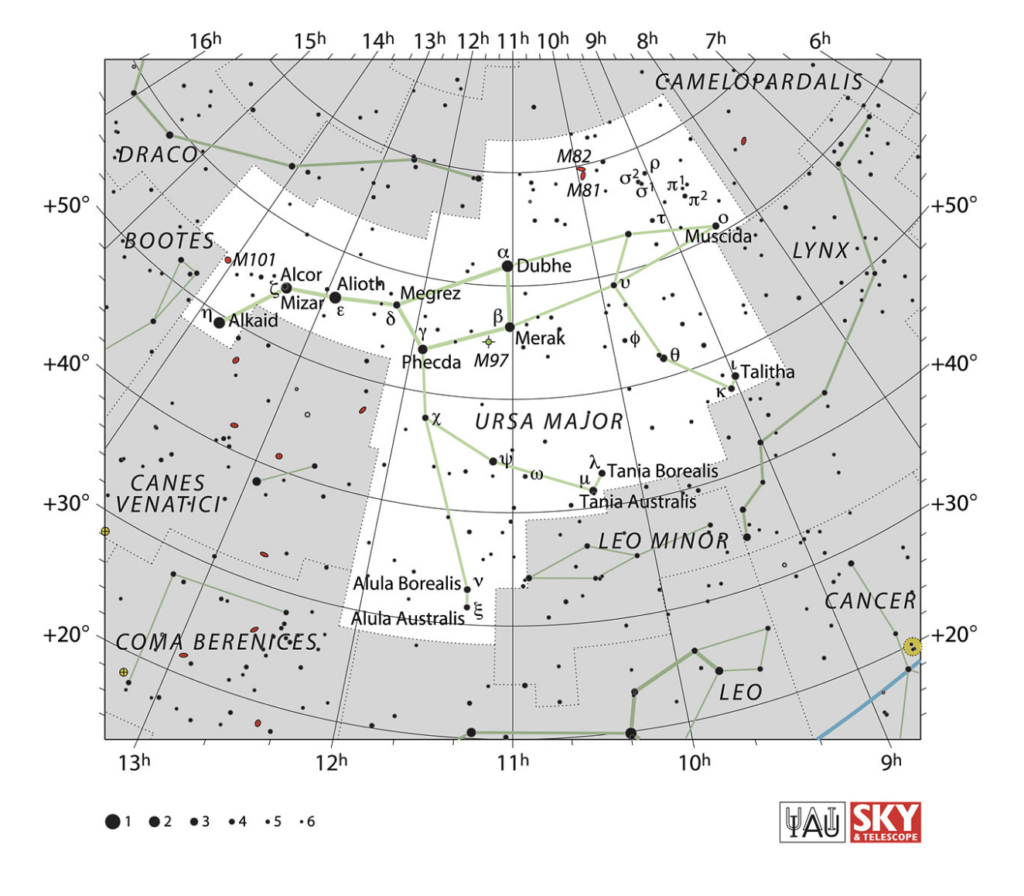

The Great Bear Constellation lies in the Northern Hemisphere’s second quadrant between latitudes +90° and -30°. Springtime makes for the most accessible viewing because of the constellation’s positioning and the likelihood of clearer skies.

Check out this interactive sky chart for your best viewing times. Just enter your zip code and press okay to see what treasures the night skies in your area hold. You can further customize the view by selecting or deselecting display options.

This and other interactive star charts simplify finding sky objects. Plus, several phone apps help you navigate the stars. So you can spend more time observing celestial objects and less time searching for them in the night skies.

Main Stars Within the Great Bear Constellation

Ursa Major holds some of the brightest (visible stars.) Here are the four most brilliant.

- The Great Bear’s brightest star is Alioth or Black Horse (not bear.) And with a magnitude of 1.76, it’s the 33rd brightest star across all the night sky.

- The second brightest star in the constellation is Dubhe, The Bear, with a 1.79 magnitude. It’s the 35th most brilliant in the night sky.

- Alkaid means “end of the tail,” and you can see from the illustration below that it indeed resides at the Great Bear’s tail. It’s the third brightest star in the constellation, with a 1.85 magnitude.

- Mizar is second from last on the Big Dipper’s handle. It’s the fourth brightest star in the Great Bear Constellation. Its name means girdle. Mizar forms a double star with Alcor, so the ancient Arabs called them the horse and rider.

The Big Dipper’s Most Notable Features

In the U.S., we know the asterism by the name Big Dipper. But it has many other names, like The Plough and The Great Wagon. Can you remember the first time you could identify this star group that’s part of the Great Bear?

In the photograph below, above Alberta, Canada’s Pyramid Mountain, are the brightest stars from left to right.

- Alkaid

- Mizar/Alcor

- Alioth

- Megrez

- Phecda

- Merak

- And Dubhe.

In most constellations and asterisms, stars aren’t physically related. But a notable feature of the Big Dipper is that its stars move in the same direction. The Ursa Major Moving Group is a star cluster about 75 light-years from Earth. The collection spreads about 30 light-years across the sky.

In addition, the stars’ measured common motion says they move at about the same velocity through space. Individual stars in the group formed around the same time as one another, about 300 million years ago.

So, now that you know Ursa Major’s location, you can observe it through your telescope (more details below.) Next, let’s get a better understanding of the constellation’s place in history.

Ursa Major in Mythology and Folklore

Astronomer Ptolemy listed Ursa Major in his 2nd century Almagest, but he called it Arktos Megale. Since its discovery, the Great Bear has been a highlight in poetry and art.

Shakespeare mentioned The Big Bear in Henry IV and Othello. Then again, he mentions it in King Lear, when Edmund feigns an interest in astronomy while speaking with Edgar. He says his conception occurred under the dragon, and his birth occurred under Ursa Major. As it turns out, he was probably right since the tail of Draco the Dragon is above the Great Bear.

The Bible even mentions the constellations of the Great Bear, Orion, and the Pleiades in Job 9:9. The references come between the 7th and 4th centuries BC. And from them, we realize the massive role of the starry heavens throughout human history.

More recently, Vincent van Gogh painted the Big Dipper in his Starry Night Over the Rhône in 1888.

Great Bear Constellation Mythology

Native American Iroquois saw the stars Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid as three hunters or warriors running after the Great Bear. One mythology version says Alioth carries a bow and arrow to kill the bear. Next, Mizar brings a large pan (Alcor) to cook the bear. Finally, the third warrior, Alkaid, carries firewood to light a cooking fire.

In addition, the Lakota and Wampanoag people also call the constellation Bear or Great Bear. But the Wasco-Wishram people believe the constellation represents five wolves left in the sky with two bears by Coyote.

It is curious that the Native American and Ancient Greek civilizations seemingly never crossed. However, both populations saw the same star cluster as a bear. The Greeks thought Zeus threw the Great Bear into the heavens.

Zeus’ wife, Hera, flew into a rage after learning that Zeus had fathered a son (named Arcas) with Callisto. She was so furious that she turned Callisto into a bear. Years later, Arcas is hunting and almost spears the bear, not realizing it is his mother. Zeus threw Callisto into the sky as Ursa Major to avoid the tragedy. But he also threw Arcas to the heavens, where he became the constellation Boötes.

Nowadays, you can see Boötes and his hunting dogs, Asterion and Chara, in Canes Venatici. The Herdsman keeps the dogs on leashes as he soars the skies in pursuit of the Great and Little Bears. You can see them the same way Johannes Hevelius imagined them in his 1687 Uranographia.

The Science Behind The Great Bear Constellation

Today, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) recognizes 88 constellations. The Great Bear Constellation is one of them. Technically, the star patterns divide the night sky to help astronomers maintain a common name and location for celestial objects.

This constellation belongs to the more vast Ursa Major constellation family. It includes:

- Boötes

- Camelopardalis

- Canes Venatici

- Coma Berenices

- Corona Borealis

- Draco

- Leo Minor

- Lynx

- And Ursa Minor.

Astronomers call the Great Bear Ursae Majoris, so the stars within the constellation get that name label. For example, Epsilon (ε) Ursae Majoris is another name for Alioth. These scientists also think most stars formed around the same period.

English astronomer and scientist Richard A. Proctor discovered the Ursa Major Moving Group (Collinder 285) in 1869. He realized all but two (Dubhe and Alkaid) of the Big Dipper stars have proper motions that head toward the constellation Sagittarius.

Quote: “I find that in parts of the heavens, the stars exhibit a well-marked tendency to drift in a definite direction.” Richard A. Proctor

What is a Moving Group?

Moving groups of stars fall between star clusters (where they formed) and field stars (not part of any group or cluster.) Star clusters may survive for hundreds of millions of years. But then they are torn apart by the gravity of nearby interstellar dust and gas clouds.

On the other hand, moving group stars are far enough apart to no longer look like a star cluster. But they haven’t drifted so far apart as the randomly distributed field stars. Moving groups also have a common or joint motion through space.

Jeremy King, a 2003 Clemson University astronomer, examined 220 potential Ursa Major moving group stars. He and his colleagues used the Hipparcos satellite’s distance determinations, velocity, and abundance measurements. As a result of their work, the team found that thirteen stars form the moving group’s nucleus, with a 14th probable member. They also determined forty-five more probable or definite members stretching across the sky.

Celestial Navigation with Ursa Major

Since the Great Bear Constellation remains visible most of the year from most of the world, it played a large part in early celestial navigation. Sailors and land travelers used the Great Bear and the Big Dipper to navigate before the invention of compasses.

Here’s how to use Ursa Major for navigation. On a clear night, find the Big Dipper. Look for the two stars (Merak and Dubhe) at the edge of the Dipper’s “pot” or “cup.” Connect a line up through them to locate Polaris. The north star is at the end of the Little Dipper’s handle, which is also the little bear’s tail in the Ursa Minor Constellation.

Polaris resides above the Earth’s north pole. So, imagine a line running through the planet and out each end of its poles. That’s Earth’s rotational axis, the line our world rotates around.

Astronomers call the spot in the sky where Polaris is closest the north celestial pole. While Earth rotates through the night, stars appear to revolve around the pole. And stars further away create a larger circle around the celestial pole.

Since Polaris is so close to the pole, it creates only a tiny circle throughout a 24-hour cycle. And since it stays in about the same place in the night sky, you can use it to find the north. Polaris appears directly overhead if you’re standing on Earth’s north pole. But looking at the star from anywhere else points you in a northern direction.

Today, robotic spacecraft and observatories use star charts to navigate. They compare the digital maps to the stars they image and measure. So, star patterns help modern navigators in much the same way as they did ancient travelers.

Using Ursa Major As a Clock

We can see the Great Bear year-round in the northern hemisphere. Because of that, you can use it as a clock! The constellation circles Polaris in a counter-clockwise direction. And it takes about 24 hours for a full rotation. So, as long as you can see Ursa Major, you have a natural clock during the night.

Hunting for Deep-Sky Objects in Ursa Major

Not only does the Great Bear Constellation contain the Big Dipper, but it also holds deep sky objects. One of our favorites is the Pinwheel Galaxy (Messier 101.) In addition to this spiral galaxy that you can likely see from your own backyard, Ursa Major is home to the

- Cigar Galaxy (Messier 82, M82)

- Owl Nebula (Messier 97, M97)

- Bode’s Galaxy (Messier 81, M81)

- Messier 40 (Winnecke 4, M40)

- Messier 108 (NGC 3556, M108)

- Messier 109 (NGC 3992, M109)

Messier 40 is not technically a deep sky object. But Messier cataloged it by mistake. M97 is a planetary nebula, and the other objects are all galaxies.

The Pinwheel Galaxy is about 70% larger than our home galaxy, the Milky Way. And it lies about 21 million light-years away. You can view it with a small telescope in the Springtime. March and April are the best viewing months.

Of course, you’ll see more detail in a dark sky area with a six or eight-inch telescope. But you can even see the Pinwheel Galaxy as a blue-and-white haze with a good pair of binoculars.

Quite a few stars in the Great Bear Constellation have confirmed exoplanets orbiting them. The numbers change regularly, as NASA has recently announced 5,500 confirmed exoplanets (as of August 31, 2023!) It’s only a matter of time before even more Ursa Major stars gain confirmation of orbiting planets.

Beyond the deep sky objects and exoplanets, the constellation is home to two meteor showers. They are the Ursids, predicted around the winter solstice, and the October Ursa Majorids predicted between October 12 and 19.

Practical Stargazing Tips for the Great Bear Constellation

Occupying a 1,280 square degree area of the night sky, Ursa Major is the third largest constellation. And you can see the Great Bear throughout the year since it is circumpolar. But some times are better than others for viewing it.

Look for the Bear constellation in spring months when it rises high above the horizon toward the northeast. Ursa Major is present in the skies from February to May. But you’ll see it best around 9:00 p.m. from April to June. That’s when it stays 50-70 degrees above the northern horizon between about 8:00 and 11:00 p.m.

Of course, dark and clear skies make for the best star observations. So try to get out of the city if you can. Check out our ten best telescopes for beginners if you’re new to sky viewing. It will teach you the basics and help you make a great purchasing decision.

Another thing we recommend is checking for a local stargazing group. People get together for viewings and usually welcome newcomers. So, if you want to make new backyard astronomer friends, they’ll help you learn to read star charts and enhance your viewing experience.

Ursa Major Today: Modern Observations and Research

The Great Bear continues captivating astronomers with its wealth of celestial treasures. One area of research focuses on the stars within the constellation. Astronomers use advanced spectroscopy and astrometry techniques to refine their understanding of star properties.

Star composition, temperature, and motion help unravel the mysteries of stellar formation and evolution. And missions like Gaia and Hubble give scientists new learning capabilities.

Another area of interest within Ursa Major is the exploration of exoplanets. The constellation’s stars are prime candidates for discovering these distant worlds through techniques like the transit method. Researchers actively search for exoplanets within the habitable zones of Ursa Major’s stars. They always hope to find environments conducive to life.

Recent astronomical discoveries within Ursa Major include the detection of new binary star systems within anciently known ones. For example, what looks like the Big Dipper’s brightest star is actually two stars, Mizar and Alcor. They were the first known binary pair. But it gets even better!

In 2010, Rochester astronomer Eric Mamajek discovered that Alcor is two stars. Mamajek and his team aimed to find new exoplanets using computer algorithms to remove the glare around the star. But instead of finding a planet, they discovered a stellar companion.

Telescope observations showed that Mizar is also a binary pair. So the ancients thought this was one star, then two stars. But now we know four stars orbit one another.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) & Ursa Major

Missions like the James Webb Space Telescope play a pivotal role in observing the Great Bear’s celestial objects with unprecedented precision. JWST’s infrared capabilities enable astronomers to peer through cosmic dust and unveil hidden details within the constellation.

When first using the space telescope, the JWST team selected a star in Ursa Major to help align and calibrate the observatory’s primary mirror. They used an isolated bright star, HD 84406, in the constellation to ensure correct imaging alignment from each mirror segment. (See combined mirror segment combined images below.)

The team also used HD 84406 to confirm the Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) could collect celestial object light.

Ongoing studies in Ursa Major involve multi-wavelength observations to uncover the intricate interplay between stars and the surrounding interstellar medium. Researchers are keen to understand the formation and evolution of stellar clusters within the constellation.

NGC3895 in the Great Bear Constellation

William Herschel spotted a barred spiral galaxy within Ursa Major in 1790. However, NASA and ESA’s Hubble Space Telescope observed it more closely in 2020. Because the telescope escapes Earth’s atmosphere, there is no distortion when imaging galaxies like NGC 3895.

In the image below, Hubble rises above Earth’s surface about 340 miles (547 kilometers.) It zips around the planet faster than 17,000 miles (27,359 kilometers) per hour, orbiting our world in 95 minutes. But it still has time to capture stunning photos like the one below of the barred spiral NGC 3895.

A Look Forward and A Look Back

Even as we look at the technological advances in observing Ursa Major, here’s a peak back in time to 1824. Samuel Leigh, England, published a constellation card set so average people could “see” the skies. What a difference from getting images today in your Instagram feed!

Leigh shows the star, Alkaid, as Benetnasch because both names shared popularity back then. But the IAU’s Working Group on Star Names later chose the more common, Alkaid, as the star’s official name.

Conclusion: The Great Bear Constellation

One of the first star groupings we learn about is the Big Dipper. Its prominence in the constellation Ursa Major and its bright stars make it easy to spot. Look for the constellation between April and June around 9:00 p.m. for the best viewing of the Great Bear.

The Bear constellation remains an active and exciting area of astronomical research. Cutting-edge technology and a growing interest in finding exoplanets within their stars’ habitable zones make Ursa Major a prime planet-hunting location.

In summary, Ursa Major is more than just a collection of stars; it’s a vital part of modern astronomy. Recent research and technological advancements have deepened our understanding of this constellation. Observatories like the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes are crucial in exploring this night sky region.

Ursa Major remains a significant piece of the cosmic puzzle, helping us grasp the universe’s fundamental principles and mysteries. And we’re excited to see where the exploration leads!